What’s on : Lectures

Event Information

Seeing is believing: Using microscopy to untangle the complexity of blood cell development.

Professor Ian Hitchcock, Professor of Experimental Haematology.

Theme Lead for Immunology, Haematology and Infection, York Biomedical Research Institute, Department of Biology, University of York

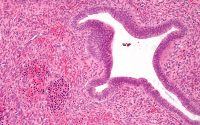

A healthy adult makes millions of new blood cells every second. Consequently, it is essential that the process of blood cell production (haematopoiesis) is tightly regulated to ensure that the right numbers and types of blood cells are in circulation at any one time, but can also rapidly respond to infection or trauma. However, when the equilibrium of haematopoiesis becomes unbalanced, the consequences are severe, potentially leading to blood cancers or bone marrow failure. Although many different factors influence haematopoiesis, a diverse family of small glycoproteins called cytokines are essential for controlling the number and type of blood cells in circulation. Using state-of-the-art super resolution microscopy, we have been able to determine how a particular group of cytokines are able to influence cell behaviour at the level of single molecules. Furthermore, this technology has allowed us to identify how these mechanisms are altered by oncogenic proteins, raising the possibility that we can now develop agents to target specific blood cancers. In this lecture, I will present our findings and consider how this work could be translated into new targeted therapies.

Member’s Report

Ian Hitchcock is Professor of Experimental Haematology at York University. Despite the scary title, his presentation was clear and (mostly) easy to understand. He started by describing the different types of blood cells and their functions. He mentioned that 99.95% of our blood cells are red and that we produce around 5 million new red cells a second. In just 24 hours, we produce twice as many red cells than there are stars in our galaxy! All of our blood cells derive from just 20,000 stem cells and these then differentiate in a cascade to produce the peripheral blood cells required. Cytokines, a type of protein, are key drivers of this process. The membrane of each blood cell has cytokine receptors. The cytokine receptors cross the cell membrane and produce a protein called Jak2 within the cell. The Jak2 then instructs the nucleus of the cell.

Ian gave a brief account of some haematological diseases and a history of the developments of treatments for them. As an illustration, he used acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. This used to be very rapidly fatal, but now has a 90% 10-year survival.

Ian then moved into his own area of research and it all became a bit more complicated. He mentioned erythropoietin, the cytokine that drives red cell production, but concentrated on thrombopoietin, the cytokine that drives platelet production. Platelets are fragments of larger blood cells, called megakaryocytes, and are critical in the clotting process. When the liver detects a low platelet count, thrombopoietin is produced and activates the cytokine receptors in the membrane of the stem cell. Jak2 then tells the nucleus of the stem cell to produce megakaryocytes. Ian’s research uses total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy to study how thrombopoietin activates the Jak2. He has discovered that two monomers (molecules) come together to form an active dimer. He showed us a video of red and blue coloured spots (representing monomers) coming together to form purple ones (representing dimers). He said that his life’s work was summarised in a 5 second video!

All of this may sound esoteric, but is of great importance for the treatment of some haematological diseases. If there is a Jak2 mutation and abnormal dimers are being produced, a medication called ruxolitinib can now be used to stop the process and control the subsequent disease.

This was a challenging topic, but if you struggled with understanding this report, the fault is mine, not that of the excellent exposition by Ian Hitchcock.

Neil Moran