William Smith

William Smith (1769 1839) – The Father of English Geology

by Rod Leonard

William Smith had strong Yorkshire connections, making it his base from the early 1820’s until his death in 1839. For most of this time, he lived in Hackness and Scarborough, and helped design Scarboroughs Rotunda Museum (1829) to display Yorkshire fossils according to the scientific principles he developed. In 1824, Smith gave a successful series of lectures to the newly formed Yorkshire Philosophical Society- this also launched the career of his nephew John Phillips. The YPS were sufficiently impressed to increase his fee from £50 to £60, and make him an honorary member. The Yorkshire Museum also has a good William Smith collection, although this is not currently on general view.

Known in his day as Strata Smith, William Smith had little education, was often shunned by the scientific establishment because of his humble origins, had his ideas stolen and his work plagiarised, and had to sell his beloved geological collection and his other assets to fund his work. He became bankrupt and spent eight weeks in a debtors prison before re-establishing himself and his reputation. He is now recognised as the Father of English Geology for his work on strata and the fossils they contain.

William Smith was born in 1769, in Churchill, Oxfordshire.

He was the eldest son of the village blacksmith, who died when William Smith was only seven. He then lived on his uncles farm and became fascinated with local fossils. He had only elementary education, but he was good at geometry. He therefore decided to teach himself surveying and then got a job with a Cotswolds master surveyor at the age of eighteen. He soon learnt the topography, water and mineral resources of Southern England and the Midlands.

He had had the ability and courage to start his own business just four years later. By 1794 he was supervising the building of the Somerset Coal Canal, and was travelling around the country to visit other canal sites. He observed that fossils of the same species were always in the same strata, that different species came in a specific order of the strata, and that this pattern was repeated in different parts of the country. Smith realised that this gave him great insight into how the geology in different regions could be put on the same time scale and could be mapped on a consistent basis using the fossil record. He therefore resolved to make a map of rock types based on fossils, and started to gather geological data from different parts of the country and to refine his knowledge of fossils. This work accelerated in 1801, when Smith was able to convert a bog into valuable agricultural land for the Duke of Bedford and thereby to get similar assignments across the country.

As his work continued, he was sponsored by Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, who recognised the commercial importance of Smiths work to the industrial revolution, and introduced potential subscribers.

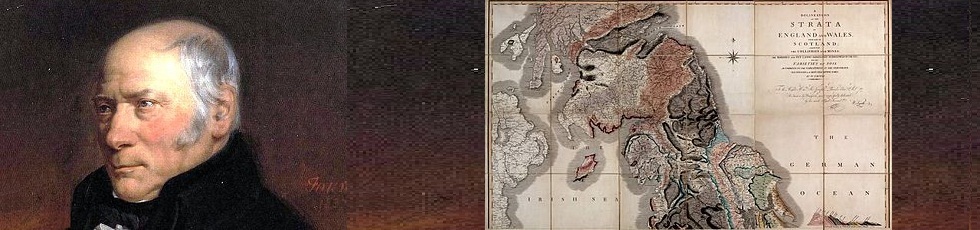

After several maps of smaller areas, the very detailed geological map A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales with part of Scotland was eventually published in 1815, and covered the country in fifteen sheets at a scale of 5 miles to the inch. In the same year he published his Delineation of the Strata of England. Jealousy within the recently formed Geological Society of London, and plagiarised cheaper copies of his work, limited his own sales to 400 copies, sold at between five and twelve pounds. The very high production costs were not met and Smith had to sell his prized geological collection for £700.

However, he continued to travel the country as an itinerant surveyor with his nephew John Phillips, who was later famous in his own right, and produced a series of 21 large scale county maps that formed his Geological Atlas of England and Wales. To finance this, he was forced to sell his remaining assets, and in 1819 he even spent time in a debtors prison. Between 1816 and 1819 he published Strata Identified by Organised Fossils.

Fair recognition did not come until 1831, when the Geological Society of London awarded him the inaugural Wollaston Medal. In 1832, King William IV awarded him a pension of £100 pa. He obtained a number of prestigious commissions, including being part of the team to select stone for the rebuilding of the Houses of Parliament. In 1835 he travelled with the British Association to Dublin, where he was awarded a totally unexpected honorary doctorate. Smith remained active until the age of 70, when he caught a sudden chill and died a few days later on 28 Aug 1839.

To find out more:

Orange, A.D. 1973. Philosophers and provincials the Yorkshire Philosophical Society from 1822 to 1844. Yorkshire Philosophical Society.

Rubinstein, D. 2009. The nature of the world the Yorkshire Philosophical Society 1822-2000. Quacks Books.

British Geological Survey website: www.bgs.ac.uk

free online Encyclopedia Britannica 9th Edition: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/549898/William-Smith

“Strange Science” website: http://www.strangescience.net/smith.htm

Image Credits:

All pictures are public domain images from Wikimedia commons